City-owned theaters and concert halls are more than just entertainment venues – they’re civic landmarks. In 2026, managing a municipal performance venue means juggling a public service mission with hard-nosed business realities. Veteran venue operators emphasize that running a government-owned venue requires both community spirit and commercial savvy. These venues must deliver cultural value to residents while keeping the books in the black – all under the watchful eyes of city councils, taxpayers, and regulators. This comprehensive guide explores how experienced managers keep municipal venues thriving by balancing mandates with revenue, navigating bureaucracy, and leveraging the unique advantages of public ownership.

The Unique Landscape of Municipal Venues in 2026

Municipal venues in 2026 occupy a distinct niche in the live entertainment ecosystem. They serve as community pillars – civic centers, historic theaters, symphony halls – often operating in a space between public good and commercial enterprise. Understanding these unique dynamics is the first step to succeeding in city-owned venue management.

Balancing Civic Mandate and Market Demands

City-owned venues typically have dual objectives. On one hand, they have a civic mandate to provide cultural access, educational programs, and community events. On the other hand, they face market pressures to host popular concerts and touring shows to generate revenue. In 2026’s competitive live events scene, even publicly owned venues must differentiate themselves to attract audiences. They’re up against private clubs, arenas, and a plethora of events vying for attention. Seasoned municipal venue managers recognize that having a public mission doesn’t exempt a venue from competition. In fact, many report feeling the heat to stand out just as much as private venues do. For example, the sheer volume of live events post-pandemic has created a crowded market, and venues must carve out a unique identity. Successfully doing so might involve specialty programming or exceptional audience experiences – any edge to remain competitive, as standing out amidst rising venue competition requires strategic differentiation. In short, a city venue must satisfy community expectations and keep its offerings exciting enough to compete in a jam-packed 2026 live entertainment market, necessitating strategies to stand out in a crowded field.

To illustrate the balance, consider a mid-sized city-owned theater that mixes free daytime community arts workshops with sold-out evening concerts. The workshops fulfill the civic duty to provide arts access, while the ticketed concerts bring in much-needed revenue. This balance is delicate – too many commercial events and the venue could be accused of abandoning its public mission, but too many free events without subsidy and the venue’s finances suffer. Successful municipal venues set clear goals that quantify both social impact (e.g. number of community events, diverse audiences served) and financial performance (revenue, cost recovery percentage). Experienced managers use these dual metrics to guide decisions, ensuring neither goal is neglected.

Turn Fans Into Your Marketing Team

Ticket Fairy's built-in referral rewards system incentivizes attendees to share your event, delivering 15-25% sales boosts and 30x ROI vs paid ads.

How Public Ownership Shapes Operations

Being city-owned changes the rulebook for venue operations. Decisions often involve multiple stakeholders – parks departments, arts councils, elected officials – rather than a single private owner. This means long-term stability in some ways (it’s rare for a city to abruptly sell off a major cultural venue), but it also means layers of oversight. Day-to-day operations might be subject to government procurement rules, civil service staffing regulations, and public budget scrutiny. For example, ordering a new sound console or renovating the lobby may require a formal bidding process and city council approval, which can slow things down.

On the flip side, municipal venues enjoy certain advantages. They might have access to city services (like police, fire, sanitation) at reduced or no cost, and they can leverage city marketing channels for promotion. Public ownership can also confer prestige and trust – residents often view the venue as “their” hall, not just a business. Managers tap into this goodwill by positioning the venue as a community asset. However, with that trust comes higher expectations for accessibility, safety, and transparency. If a private club has a bad night with long lines or technical issues, it’s seen as a one-off problem; if the city’s premier concert hall has the same issue, expect headline news and tough questions at the next council meeting.

Ready to Sell Tickets?

Create professional event pages with built-in payment processing, marketing tools, and real-time analytics.

Key Differences Between Municipal and Private Venues:

| Aspect | Municipal Venue (City-Owned) | Private Venue (Commercial) |

|---|---|---|

| Mission/Purpose | Public service, cultural enrichment, community access | Profit-driven, entertainment and business goals |

| Ownership | Government (city, state, or public authority) | Individuals, promoters, or corporate entities |

| Funding | Mix of revenue and public funds (subsidies, grants, taxes) | Primarily ticket sales, F&B, sponsorships, private capital |

| Oversight | Political oversight (city council, public boards, auditors) | Owner/board oversight, market forces, investors |

| Decision Speed | Slower – subject to bureaucracy and public process | Faster – can act on business needs quickly |

| Accountability | High transparency; must justify decisions to public | Accountable to owners/investors; less public transparency |

| Labor | Often unionized or city staff; civil service rules | Mix of non-union and union; private HR policies |

| Example | City-run Civic Auditorium or Town Hall Theater | Privately-run nightclub or commercial arena |

As the table shows, municipal venues operate under greater public accountability and often rely on mixed funding sources. They can’t pivot as nimbly as private venues, but they also aren’t solely at the mercy of the bottom line. Wise managers learn to work within these parameters – leveraging the perks of public ownership (like grants or city services) while mitigating the constraints (like bureaucracy and slower processes).

Public Expectations and Community Accountability

City-owned venues are fundamentally accountable to the public. This accountability goes beyond just financial reporting. Community members and local politicians pay close attention to programming choices, ticket prices, even the diversity of artists and events hosted. A municipal concert hall isn’t just evaluated on ticket sales – it’s also judged on how well it reflects the community’s needs and values.

For example, if a city-run theater hosts only high-priced touring Broadway shows and neglects local performers or affordable events, the public might push back. On the other hand, if it runs many free community events but then faces huge financial losses, taxpayers will ask tough questions. Veteran operators note that finding the “sweet spot” is crucial. Many venues form Community Advisory Boards or solicit public feedback to stay aligned with local expectations. In practice, this could mean hosting town-hall style meetings about upcoming seasons or inviting community arts groups to help shape programming.

Keep Tickets in Fans' Hands

Our secure resale marketplace lets attendees exchange tickets at face value, eliminating scalping while keeping you in control of the secondary market.

One seasoned venue manager recounts how public feedback directly impacted their schedule: “We realized our calendar had plenty of rock concerts but very few family events. In response to community input, we added monthly family movie nights and weekend children’s theater shows – at low ticket prices – to welcome more local families.” This kind of adjustment builds goodwill and proves the venue is listening. It’s also strategic: engaging families and diverse audiences today cultivates the next generation of patrons, ensuring long-term support.

Finally, transparency is part of public accountability. Municipal venues often publish annual reports highlighting not only financials but also community impact metrics – number of local artists featured, free tickets distributed to youth, economic impact on local businesses, etc. This data can be powerful. For instance, when lobbying for continued funding, a venue can demonstrate that for every £1 of city funding, it generated £5 in local economic activity through tourism, jobs, and vendor spend. By clearly communicating such benefits, managers build a case that the venue is a worthy public investment, not a financial drain.

Public Service Mission vs. Financial Sustainability

Perhaps the greatest challenge in municipal venue management is walking the tightrope between public service and financial sustainability. In 2026, cities are demanding that venues justify their budgets, yet they also expect these venues to offer inclusive, affordable programming. Achieving both aims requires creative strategies and smart planning.

Mandating Access While Meeting the Bottom Line

City-owned venues usually have mandates to ensure accessibility and affordability for local residents. This can translate to offering discounted tickets for seniors, students, or low-income patrons, and hosting a certain number of community or educational events each year. Some venues are even required by their funding agreements to keep ticket prices for certain events below a threshold. These policies uphold the public mission – but they also can limit revenue potential.

To balance this, municipal venue managers often employ innovative approaches to accessibility that don’t break the bank. For instance, many have embraced tiered pricing models and creative ticketing options. Early-bird discounts, family bundles, and pay-what-you-can nights allow people of different income levels to attend. In 2026, some forward-thinking venues are even offering installment payment plans for pricier shows, letting fans spread the cost over time. By offering buy now, pay later ticket options to ease affordability barriers, city venues can welcome more attendees without needing an outright subsidy for every ticket. These measures demonstrate a commitment to inclusion while still ultimately collecting the ticket revenue.

Another tactic is balancing expensive headline events with free or low-cost programming under the same roof. For example, a municipal performing arts center might host a lucrative touring Broadway production one week and a free local school choir performance the next. Revenue from the commercial event effectively subsidizes the free community event. Many veteran managers schedule “one for them, one for us” in their calendars – meaning for every high-grossing commercial booking, they plan a community-focused event. This ensures the venue meets its social mandate without constantly draining public funds.

Crucially, transparency in pricing builds trust. City venues have been at the forefront of the movement to eliminate hidden charges, knowing that nothing angers patrons (and their council representatives) more than surprise “junk fees.” By embracing transparent ticket pricing without hidden fees, public venues demonstrate respect for their audience. Some have even lobbied to include all fees in the advertised price or absorbed small processing costs to keep the experience straightforward. The goodwill earned with the public often translates to repeat attendance and political support, which in turn bolsters financial stability.

Revenue-Generating Strategies for City Venues

Achieving financial sustainability means diversifying revenue streams. Municipal venues cannot rely solely on ticket sales – especially when they offer so many community benefits that might not be profit-makers. Leading venues in 2026 are tapping into a mix of income sources:

Grow Your Events

Leverage referral marketing, social sharing incentives, and audience insights to sell more tickets.

- Ticket Sales & Rentals: Of course, selling event tickets is primary. But city venues also generate income by renting the space for conferences, corporate events, or film shoots on dark days. A grand city hall auditorium might host a tech company’s annual meeting for a hefty rental fee, for instance.

- Food and Beverage (F&B): Upgraded concessions and even full-service restaurants or bars in venue can significantly boost revenue. Patrons at a city-owned theater in Melbourne or Manchester will happily arrive early for a drink if the ambiance is right. Veteran operators focus on optimizing F&B operations – from reducing bar wait times to offering local craft beverages – to increase per-visitor spend.

- Merchandise & Ancillary Sales: City venues often partner with artists to sell merchandise, taking a percentage of sales. Some venues have gift shops featuring local artisans or venue-branded souvenirs (especially if the venue is historic or iconic). These add-ons can contribute modest but meaningful income.

- Sponsorships & Naming Rights: While more common in arenas, even theaters and concert halls explore sponsorship deals. It could be as subtle as a local bank sponsoring a classical concert series, or as visible as selling naming rights for a new wing or season. Public venues have to tread carefully here – sponsorships must align with the venue’s public image (a fast-food sponsor for a children’s theater program, for example, might raise eyebrows). But done tastefully, sponsor dollars can underwrite community programming. Some cities have embraced this: e.g., the Ticketmaster Performing Arts Center approach, but in 2026 many are cautious, preferring local or arts-aligned brands over purely commercial names.

- Public Funding & Grants: Yes, this is revenue too – direct operating support from city budgets, or grants from national arts councils, etc. We’ll delve more into leveraging these in the next section, but savvy managers treat public grants as one line of the revenue mix, not a given to be wasted.

Experienced operators also keep a close eye on costs to maximize net revenue. They implement internal controls to prevent theft and loss in venue operations – for example, using point-of-sale systems that track every sale and inventory controls that flag any bar shrinkage or missing merchandise. A dollar saved by tightening operations is just as valuable as a dollar earned in sales, especially under government scrutiny. By minimizing waste and loss, venues retain more of their hard-earned income to reinvest in community programs.

Sample Programming Mix: Balancing Mission and Revenue

| Event Type | Benefits to Venue & Community | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Free Community Festival | Fulfills public mandate; builds goodwill and access. Engages local artists and families. |

Requires subsidy or sponsor to cover costs. No direct revenue from tickets. |

| Touring Broadway Musical | High ticket revenue; attracts tourists and regional visitors. Boosts local economy on show nights (restaurants, parking). |

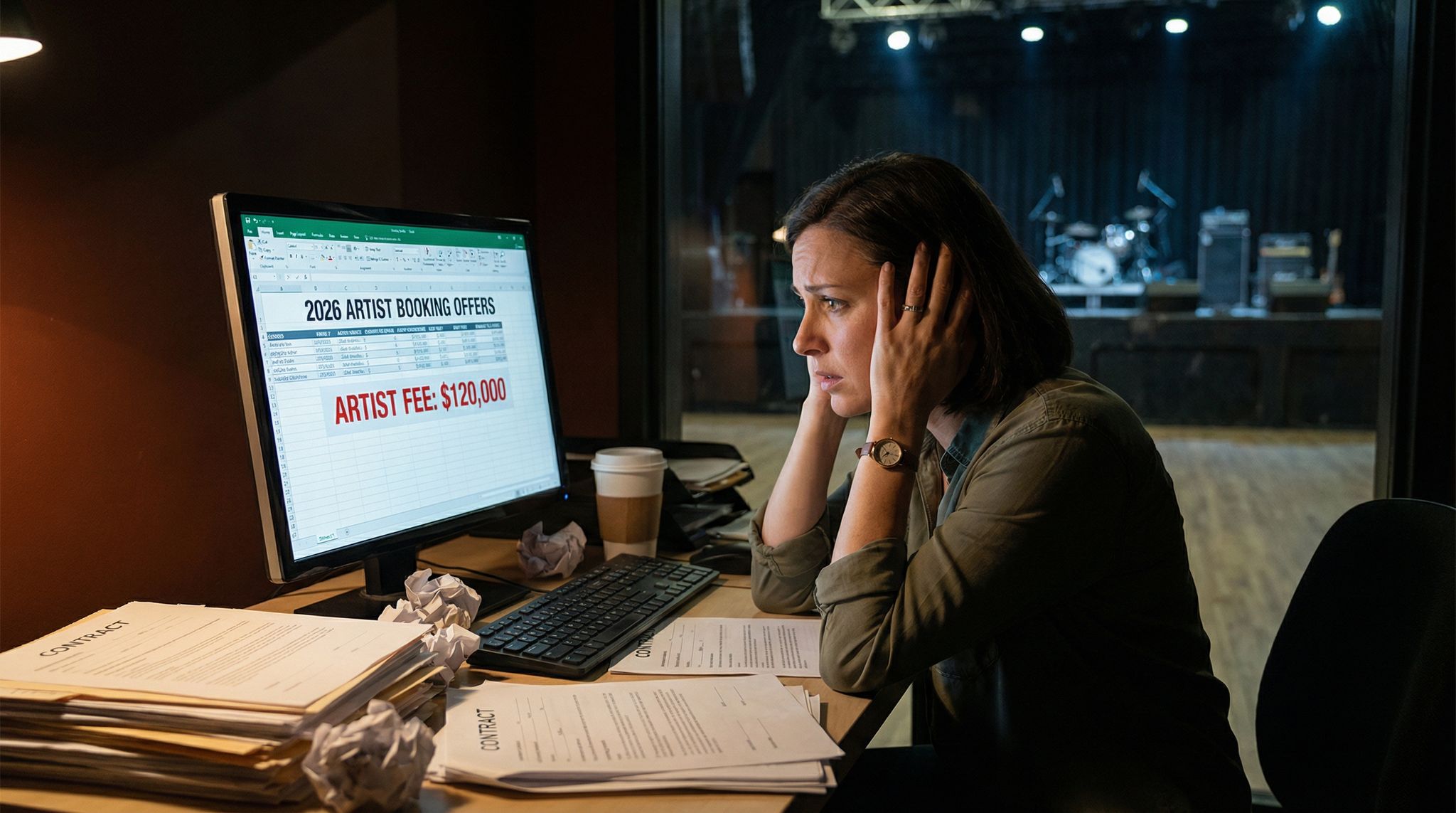

Expensive guarantee or fee to book. Tickets may be pricey – ensure some affordable options to avoid criticism. |

| Local School Concert | Strengthens community ties; youth arts education. Parents and schools become advocates for the venue. |

Low or no revenue; staff still needed for production and supervision. Can schedule on off-night to avoid displacing revenue events. |

| Comedy Night (Off-Night Programming) | New audience segment; fills an otherwise dark night. Revenue from bar sales and moderate ticket prices. |

Must adjust production (different tech needs, seating formats). Marketing to comedy fans required. |

| Corporate Event Rental | Significant rental fee; minimal effort (external event team often handles logistics). Introduces venue to new audiences (attendees who may return for public shows). |

Venue not open to public during event. Need to maintain brand/image (ensure event aligns with venue’s values and doesn’t cause damage). |

| Outdoor Summer Concert (if applicable) | Wide community reach; can accommodate larger audiences. Opportunity for food trucks and beer garden revenue. |

Weather and logistics challenges. Noise and neighborhood considerations – requires community outreach and compliance with permits. |

In practice, municipal venue managers craft a varied calendar like the above, ensuring the profitable events subsidize community-centric ones. For example, a wildly successful Broadway tour’s profit might pay for a month of free local events. By showing this cross-subsidy in budget reports, managers can demonstrate to officials that they’re stretching public dollars to achieve cultural outcomes.

Optimizing Venue Utilization and Calendar

Given their financial constraints, city-owned venues strive to maximize utilization. An idle venue is a missed opportunity, both mission-wise and revenue-wise. The goal is to minimize “dark” days when the hall sits empty. Multi-use flexibility is key – a council-run venue may host a ballet one night, a business conference the next morning, and a rock concert the following evening. Pulling this off is challenging, but veteran operators have developed systems to make rapid turnovers possible. Many of these best practices are shared across the industry: for instance, executing rapid event changeovers with minimal downtime is now a core competency for top venues. They use standardized stage setups, modular seating configurations, and well-drilled crew teams to flip the space quickly. A prime example is a city arena in Canada that hosted a hockey game and a concert in the same 24 hours – an extreme case, but it shows what’s doable with planning.

Efficient calendar management also means being strategic about booking dates. Municipal venues often have to accommodate civic events (like a Mayor’s address or public ceremonies) that can block prime dates. Experienced managers negotiate and plan far in advance to minimize impact. For example, if the city insists on holding graduation ceremonies each June weekend, the venue can work with promoters to concentrate concerts in July and August or find creative ways to double up usage (perhaps using a secondary space for smaller events concurrently).

Additionally, municipal venues are learning to be more flexible in their programming to seize opportunities. A decade ago, a city-owned theater might have stuck rigidly to a classical music series and ignored popular entertainment. In 2026, agile managers will jump on a hot trend if it aligns with their space – be it a viral YouTuber’s live show, an eSports tournament, or a themed immersive experience – if it fills seats, it’s on the table. One New Zealand city hall, for instance, started hosting video game music concerts and saw a surge of first-time younger attendees. This doesn’t mean abandoning the mission; it means expanding the definition of performing arts to stay relevant (while still hosting the traditional symphony and theatre productions too). The mantra is versatility: the more types of events your venue can accommodate, the better you can fill the calendar and meet both revenue and community goals.

Navigating Government Bureaucracy & Politics

Running a municipal venue often involves as much politics as show business. Unlike private venues, you can’t just make every decision in-house – you’re enmeshed in government processes. Navigating bureaucracy and political oversight is a critical skill for municipal venue managers in 2026.

Working Within Government Structures

City-owned venues usually fall under a specific government structure or department. Some are part of a Parks & Recreation department, others under Arts & Culture agencies, and some large venues might be their own public authority. This structure means decisions are subject to government rules. Common examples:

- Procurement Policies: Need new stage lighting or to contract a cleaning service? Municipal rules often require issuing RFPs (Requests for Proposals) or getting multiple bids, especially for large expenditures. Managers must budget extra time for these processes. It’s not glamorous, but mastering the art of writing clear RFPs and working with purchasing departments is key to keeping the venue equipped without undue delays.

- Hiring and HR: Venue staff might be city employees. This can provide stable jobs with benefits (good for staff morale), but hiring often has to follow civil service exams or union rules. Firing underperforming staff can be difficult due to government employment protections. Veteran managers stress training and upskilling existing staff since you can’t always just hire a specialist from outside quickly. Many invest in cross-training city employees in technical theater skills or customer service, rather than trying to bring in contractors at the last minute (which might require additional approvals anyway).

- Budget Approvals: Annual budgets likely need city council approval. This means each year, the venue’s financial plan is under a microscope. Savvy managers prepare detailed justifications for expenditures and, importantly, show how those align with city priorities (e.g., “This $100,000 for new sound equipment will enable us to host more community events and generate $150,000 in additional ticket revenue over two years”). Having allies in the council or a champion in the mayor’s office who understands the venue’s value can make budget season far smoother.

It’s not just red tape for its own sake – these structures are in place to ensure public funds are spent responsibly. The trick is to find flexibility within the rules. For instance, some city venues keep a small discretionary fund (approved by council) for emergency needs so they don’t have to do a full procurement every time a cable breaks. Others create pre-approved vendor lists to expedite routine purchases. The bottom line: know the rules inside out, then work creatively within them.

Political Oversight and Relationship Management

Municipal venues answer to multiple stakeholders, including elected officials. A city council or a board of trustees likely oversees the venue’s direction, sometimes making strategic decisions or even getting involved in programming choices if an event becomes controversial. Venue managers often become diplomats and educators, ensuring that political overseers understand industry realities.

Building relationships with city leaders is crucial. Seasoned venue operators make a point to invite council members, mayors, or cultural ministers to key events – not just as ribbon-cutters, but to experience a successful show or see a community program firsthand. When officials see a theatre full of happy families on a free kids’ day, or a concert that brought in tourists, it personalizes the venue’s value. One operator of a city-owned hall in Germany would send a brief after-action report to city officials for major events, highlighting attendance numbers, positive patron feedback, and any notable VIPs or press coverage. This proactive communication keeps stakeholders in the loop and shows that the management is responsible and effective.

Political oversight can sometimes veer into political interference. Managers must be prepared for changing directives, especially after elections. A new mayor might want the venue to focus more on certain community outcomes or could question a long-standing commercial partnership. There have been cases where political figures push pet projects – like hosting a sister city’s orchestra for a special performance – that the venue must accommodate, even if it’s not profitable. The strategy here is to stay flexible and find the win-win. If you’re asked to host a non-revenue event under political pressure, see if you can secure additional city funding or sponsorship to cover it, or schedule it on a date that doesn’t bump a paying client.

Above all, maintain the venue’s reputation as a well-run public asset. If controversies arise (say, a public outcry over a canceled show or a contentious artist booked at the venue), having a reservoir of goodwill with both the public and officials will help. An example comes from a U.S. city-owned amphitheater that booked a hard rock festival which drew noise complaints. The following council meeting was heated. But the venue manager had proactively shared data: the festival brought in $2 million to local businesses and the venue had followed all permit rules. They also met with neighborhood groups to outline new noise control measures for next time. This balanced approach appeased the council, and the venue was allowed to continue with only minor adjustments rather than losing rock concerts altogether. Political navigation in 2026 is about transparency, compromise, and constantly demonstrating public value.

Surviving Budget Cycles and Public Scrutiny

Municipal venues live and die by budget cycles. Every fiscal year (or every few, if on a multi-year budget plan) you need to justify your funding. Unlike a private venue that can reinvest profits or take a loan, a city venue often relies on the council’s allocation for capital improvements or even operating support. Economic swings add pressure – in lean times, arts and culture budgets are often first on the chopping block.

One challenge is that cultural ROI is harder to quantify than pure revenue. However, data can be your ally. Many venues now collect solid metrics on their impact to bolster their budget requests. These include economic impact studies (showing how many jobs the venue supports and how much spending it generates citywide), community impact stats (such as number of free events, youth reached, volunteer hours, etc.), and comparative benchmarks. For instance, a venue manager might present: “Our theatre operates at 70% cost recovery through earned income, above the national average of 60% for similar municipal theaters.” Such stats, drawn from industry reports or associations like IAVM, frame the venue as a high-performing asset rather than a drain.

It’s also smart to align venue goals with political priorities. In 2026, many cities have goals around economic recovery post-COVID, diversity and inclusion, and climate sustainability. Municipal venues can contribute to all three, and managers should make that known. Highlight how the venue is aiding downtown economic recovery by drawing visitors, how it’s amplifying diverse voices by programming artists from underrepresented communities, or how it’s gone green with energy-efficient lighting (more on sustainability later). This alignment makes it politically easier for officials to justify funding the venue. It transforms the narrative from “the city subsidizes entertainment” to “the city invests in community well-being and growth through this venue.”

Sometimes, despite best efforts, cuts come down. We’ve seen sobering examples recently – Berlin, a city famed for its cultural spending, announced a €130 million cut to its arts budget (roughly 12%) in 2024. This sent shockwaves through theaters and opera houses; around 450 cultural institutions reliant on public subsidies formed an alliance to protest the cuts, as reported by The Guardian on Berlin’s arts budget crisis. While this is an extreme case, it underlines that no venue is immune to economic realities. To survive such cuts, venues may need to adapt: reduce schedules, find temporary funding from donors, or share resources with other institutions. Importantly, they must communicate transparently with the public about what a cut will mean. If hours are reduced or programs trimmed, frame it honestly – e.g. “Due to city budget reductions, we must pause our free concert series this year, but we’re actively seeking grants and partnerships to bring it back.” Communities can be surprisingly understanding if you bring them into the loop, and they might even rally to help (through fundraising or advocacy) when they see their beloved venue under threat.

On the flip side, when prosperity allows, municipal venues should be ready with shovel-ready projects to propose. If a government stimulus or surplus comes along, having a ready plan for that long-needed renovation or new community program increases the chance of securing funding. For example, the Tennessee Performing Arts Center (TPAC) in the U.S. recently secured a massive commitment from the state: $500 million in public funding (over two budget cycles) to build a new modern facility, contingent on raising private contributions as well, a strategy detailed in IAVM reports on state grant funding. This kind of opportunity only materializes if venue leadership has done its homework with feasibility studies and demonstrating why the investment is necessary (in TPAC’s case, an antiquated building and evidence that renovation costs would rival new construction). The lesson: always have a vision in your back pocket and the justification ready, so you can seize political and funding opportunities when they arise.

Funding, Subsidies, and Public-Private Partnerships

Financing a municipal venue is often a patchwork quilt of sources. While private venues rely on investors or profits, public venues mix government subsidies, grants, donations, and earned income. In 2026, creative funding models and partnerships are helping city venues bridge budget gaps without sacrificing their public mission.

Maximizing Public Funding & Grants

Direct government subsidy is the cornerstone for many municipal venues. This could be an annual operating budget from the city or periodic capital funding for upgrades and maintenance. To maximize this lifeline, successful venues treat public funds with high responsibility and seek out additional grants aggressively. National and regional arts councils, for instance, offer grants for specific purposes (educational outreach, facility improvements, digital innovation, etc.). Europe has EU cultural grants; the U.S. has National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grants; many countries have similar bodies. A well-resourced venue often has a grant writer on contract or staff to pursue these opportunities.

In recent years, we’ve seen how vital grants and relief funds can be. The pandemic era (2020-2022) was a wake-up call: emergency relief like the U.S. Shuttered Venue Operators Grant or the UK’s Cultural Recovery Fund saved countless venues from collapse. Going into 2026, blanket bailouts are over, but targeted aid is still available – if you know where to look and how to win it. Managers share that they’ve learned to tap into lifeline funding sources such as local economic development grants or tourism boards looking to sponsor events that draw visitors. For example, a city tourism bureau might fund an international festival at the venue to boost travel.

Many veteran operators recommend building a diversified “grant portfolio”. Don’t rely on just one source. One year a national grant might come through, another year it might be a private foundation’s arts grant. By spreading out, you reduce the shock if one source dries up. It’s also wise to document every success that results from grant money – that strengthens future applications. If you got a $50,000 grant for a youth music program, be ready to report that it enabled 20 free workshops, trained 100 young musicians, and led to 5 students pursuing music studies. Hard evidence of community impact can secure renewals and new grants.

For a deeper dive into unlocking these funds, venue managers can refer to guides like securing arts grants, government relief, and community funding for venue survival. Such resources outline where to find grants and how to write winning applications, often with real examples of venues saved by fan donations and public support. The key takeaway is that money is out there, but you must proactively chase it and align your proposals with the funder’s goals (which often dovetail with your public mission anyway).

Cultivating Sponsors, Donors and Friends

Beyond government money, municipal venues are increasingly looking at private sector and community contributions to shore up finances. This can range from corporate sponsorships to individual philanthropy and volunteer fundraising.

Corporate sponsorship in municipal venues is a sensitive dance. Unlike a sports arena, you won’t usually see a city opera house plastered with logos. But there are subtle, effective ways to partner. Many city orchestras and theaters have seasons or series underwritten by companies (“Symphony Series presented by XYZ Corporation”). Companies often like supporting the arts as it bolsters their image, especially if they’re local businesses. The key is ensuring the sponsorship recognition is tasteful and in line with public expectations. A city-owned concert hall might have a donor wall in the lobby thanking major sponsors and patrons, or include sponsor mentions in programs and pre-show announcements, which is plenty to keep them happy.

Individual donors are another pillar. Friends of the Venue programs are common: for an annual donation, patrons get perks like early access to tickets, special events, or their name on a seat plaque. While it may feel odd for a “public” venue to ask citizens for donations (after all, aren’t taxes paying for it already?), the reality is that many people are willing to give extra to ensure their local theater thrives. These membership or “friends” schemes can bring in tens or hundreds of thousands annually, all earmarked for programming or education initiatives. Importantly, they also deepen the patrons’ personal investment in the venue’s success – those donors become vocal advocates in the community and to politicians.

Some municipal venues have associated 501(c)(3) nonprofit foundations or trusts specifically to handle fundraising. This is an effective structure: the venue operates day-to-day under the city, but a separate nonprofit can solicit tax-deductible donations and even manage an endowment for the venue. Examples include many U.S. performing arts centers (often the city owns the building while a nonprofit runs it and raises funds). This hybrid model leverages the stability of public ownership with the fundraising versatility of a private entity. It’s public-private partnership in practice.

A case in point: in New York City, the historic Kings Theatre in Brooklyn was a city-owned derelict movie palace that was revived through a public-private partnership. The city invested heavily in restoration, but a private operator (and private capital) was brought in to run it, and a nonprofit “Friends of Kings Theatre” was formed to engage the community. The result has been a flourishing venue that hosts major concerts and local events alike. Such models can be win-win – public goals met with help from private expertise and funding.

Innovative Partnership Models (Management Contracts & More)

Not every city has the in-house expertise or resources to run a venue directly. That’s where alternative operating models come in. Management contracts, venue leases, and hybrid ownership structures are increasingly common in 2026, especially for large or complex venues like arenas and convention centers.

Under a management contract, the city retains ownership of the venue but hires a professional venue management company (often one of the global firms like ASM Global, Live Nation, or AEG Presents, or a specialized local operator) to handle day-to-day operations and bookings. The contractor is paid a fee or a share of revenue, and specific performance targets may be set (such as minimum number of events, revenue thresholds, maintenance standards, etc.). This approach can bring in private-sector efficiency and industry connections – for instance, a management firm might secure better deals on talent due to their network and negotiate volume discounts on equipment across venues they manage. The city of Los Angeles famously uses this model for certain facilities: the Greek Theatre (owned by the city) has at times been operated by private companies under contract. The key for success is a well-crafted contract aligning the operator’s incentives with the public interest (e.g., requiring a certain number of community events or setting caps on ticket fee markups to keep shows accessible).

Another model is a long-term lease or concession. Here, a private entity might lease the venue from the city for a period (say 10 or 20 years), taking on more risk but also more autonomy. In exchange, the city might receive a fixed rent or a percentage of profits. This is more common when a venue needs major investment that the city can’t afford – a private lessee may agree to renovate or upgrade the facility as part of the deal. However, from the public’s perspective, it can feel like “privatization,” so it’s often used carefully (or for venues that are less central to civic identity). When done right, it injects capital and expertise while keeping the asset ultimately under public ownership. For example, in some UK towns, historic theaters are council-owned but operated by Ambassador Theatre Group (ATG) on leases; ATG brings in big shows and runs the business, while the council ensures the building is preserved and accessible to local groups on occasion.

There are also non-profit operation models: the city owns the building but a non-profit organization runs it (often with a board that includes city appointees). This can unlock fundraising (as mentioned above) and sometimes is a more palatable structure for arts-oriented venues where mission alignment is key. The city’s role shifts to being a partner-funder rather than direct manager.

No one model is inherently superior – it depends on the city’s capacity and goals. The trend in 2026 is toward flexibility. Some cities directly run smaller community theaters in-house (where the focus is more on local programming and the scale is manageable), but contract out the management of a large arena or concert hall (where commercial acumen is crucial). Importantly, even when contracting out, the city typically retains oversight via contract compliance checks and keeping certain decision rights (for example, approving the annual event schedule or capital improvements).

When a venue owned by a municipal government brings in a major private operator, the goal is often to modernize the patron experience and maximize utilization. Civic leaders increasingly want to transform aging civic auditoriums into dynamic, immersive entertainment venues. They recognize that relying on rigid designs or settling for generic experiences won’t cut it in today’s competitive market. For instance, when global management firms like ASM Global take the reins of a city-owned facility, they are typically tasked with reimagining the space to support cutting-edge event formats that draw regional tourism. Similarly, when evaluating operational tech, municipal boards look closely at how industry giants operate. They note how promoters like AEG Presents utilize ticketing platforms that ensure the system has ample inventory controls to handle everything from a 50-person VIP civic reception to a 10,000-ticket outdoor festival seamlessly.

Common Municipal Venue Operating Models:

| Operating Model | Key Features | Example Instance |

|---|---|---|

| Direct City Department | City agency manages all operations; staff are city employees; budget is part of city budget. High public control, but can be bureaucratic. |

Small City Civic Theaters, e.g., a town-run Community Arts Centre where Parks & Recreation oversees programming. |

| Non-Profit Organization | City owns facility but a dedicated non-profit (with its own board) operates it. Non-profit can fundraise, but city often provides subsidy or oversight seats on board. |

Many performing arts centers (e.g., Miami’s Arsht Center) – building by county, run by a trust that raises funds and hires staff. |

| Private Management Contract | City contracts a venue management firm or promoter to run venue for fee or revenue share. City sets performance targets and retains ownership; private operator brings expertise in bookings and operations. |

Greek Theatre in Los Angeles (city-owned, privately managed under contract); numerous convention centers and arenas globally. |

| Long-Term Lease/Concession | City leases venue to private entity for X years. Operator may invest in improvements, has greater autonomy; city gets rent or profit share. Less day-to-day control for city during lease term. |

UK example: Venue Cymru in Wales was leased to an operator; or privatized management of stadiums via long concessions. |

| Hybrid Joint Venture | City co-owns or co-manages with another entity (could be state government or university). Shared responsibilities; often done for multi-use complexes. |

Some Australian arts precincts involve city + state partnerships, or a city teams up with a university that uses the venue for its arts program. |

Choosing a model is often driven by financial necessity or a desire for professional expertise. A struggling municipal venue might actually benefit from bringing in an outside operator to turn it around – as long as public interests are safeguarded. Conversely, a city may take operations in-house if they feel a private operator isn’t serving the community aspect (this happened in a few cases where cities did not renew a private contract because the venue was programming only blockbuster events and ignoring local arts). In 2026, the best approach is often a well-regulated partnership: use private-sector efficiency, but hold them accountable to public-service outcomes.

Shared Vision: Aligning Stakeholders for Success

Whatever the funding or management model, a recurring theme for success is alignment. All stakeholders – city officials, venue management, staff, artists, sponsors, and the community – should share a vision of what the venue is meant to be. This vision can be formalized in a mission statement or strategic plan, but it needs to live in daily practice. If everyone knows “we’re here to provide world-class entertainment and community cultural enrichment while operating sustainably,” then decisions about booking, spending, or partnerships become clearer.

One practical tip veteran managers offer is to develop a cultural policy or charter for the venue in collaboration with the city. This document might outline the venue’s commitments (e.g., a certain percentage of local content, a pledge to diversity in programming, affordability measures, etc.) alongside financial performance goals (e.g., target cost-recovery ratio, attendance numbers). By agreeing on this framework, you preempt a lot of conflicts – political overseers see that you’re meeting the agreed mission, and you have cover to make commercially smart moves as long as you hit those community commitments.

Take the example of Sydney Opera House in Australia. As an iconic government-owned venue, it operates under a Trust with a clear mandate to both present the finest performances and engage the public. The NSW state government invests heavily (including a recent A$202 million renovation commitment by the NSW government to upgrade the Opera House’s facilities, marking the first major facelift since 1973), but in return expects the Opera House to be accessible and beneficial to all Australians. Through careful planning, the Opera House Trust delivers – they host everything from the Sydney Symphony and Opera Australia to community arts festivals and outdoor events – a broad vision realized through strong stakeholder alignment. The public funding was justified by the venue’s wide reach and careful stewardship of a national icon.

Community Engagement & Cultural Impact

City-owned venues ultimately belong to the community, so deep engagement with local audiences and organizations is essential. Financial viability means little if a municipal venue loses the support and interest of its citizens. Here we explore strategies for keeping the community at the heart of a public venue’s operations.

Serving Diverse Community Needs

A municipal venue must reflect its community’s diversity – in the artists on stage, the audiences in the seats, and the types of events offered. Veteran operators stress that programming must be inclusive and responsive. In practice, this means booking a wide variety: theatre, music of all genres, dance, film screenings, multi-cultural festivals, you name it. A city-owned hall in a diverse city like Toronto or London might host a Caribbean music fest one week, a Diwali celebration the next, followed by a classical European opera – showcasing the spectrum of local cultures.

Engaging diverse audiences also requires removing barriers. This includes economic barriers (as discussed earlier with affordability initiatives) and cultural barriers. For example, some people may feel a grand concert hall “isn’t for them.” To counter that, municipal venues run outreach programs: perhaps partnering with community centers to bring groups to their first show, or literally taking performances out to neighborhoods (like a traveling summer concert series in city parks that then invites attendees to visit the main venue). Furthermore, scheduling events at different times can help – not everyone can attend a night show, so why not a weekend matinee for families or weekday morning concerts for seniors?

Special initiatives often make a real difference. An example is relaxed performances or autism-friendly shows which some city theaters have introduced – lighting and sound are adjusted, audiences can move around, making it comfortable for those with sensory sensitivities. Another is multilingual programming and marketing in cities where multiple languages are spoken, ensuring that promotional materials and even on-site signage make everyone feel welcome.

One area municipal venues excel is providing a platform for local talent. Community theaters, amateur orchestras, school plays – a city stage often hosts these alongside professional productions. This isn’t just charity; it’s cultivating local arts ecosystems. Today’s high school band on your stage might produce tomorrow’s superstar who remembers that early opportunity. Plus, when local performers take the stage, they bring their own audience (friends, family, fans) who might not otherwise visit the venue. It’s a built-in community engagement booster.

Education and Outreach Programs

Education is frequently part of a public venue’s charter. Many city-owned concert halls and theaters run robust educational outreach, seeing it as core to their public service. This can include:

- School Matinees & Tours: Coordinating with schools to bring students in for daytime performances or behind-the-scenes tours. For instance, an orchestra might do a shortened version of a symphony with an interactive presentation for thousands of schoolchildren each year. It might be low or no cost to the schools, funded by the venue’s education budget or sponsors.

- Workshops and Masterclasses: Visiting artists can be engaged to conduct workshops for local youth or community choirs/dance groups. Veteran venue managers ensure contracts with performers include (when possible) a community engagement component – many artists are happy to oblige, doing an afternoon Q&A or clinic, which greatly amplifies the impact of their visit.

- Internships and Training: Some municipal venues offer internship programs or apprenticeships in technical theater, event management, or arts administration for local students. This not only helps the venue with extra hands and builds good community relations, it also addresses industry workforce development. In 2026, as the live events sector continues rebounding, training new talent is a worthy investment.

- Community Partnerships: Collaboration with local arts organizations is a hallmark of outreach. For example, a city venue might partner with the municipal library on a summer reading and theater program, or with a local music school to showcase young musicians. These partnerships can provide content for the venue (filling otherwise empty dates) and fulfill mutual goals of community enrichment.

A powerful benefit of education programs is that they cultivate future audiences. A child who has a magical experience watching a play at the city theater or playing on its stage is more likely to become a ticket-buyer or donor as an adult. It’s sowing the seeds for the cultural appreciation that justifies the venue’s existence for generations to come.

During the pandemic, many venues learned to extend outreach digitally – streaming educational content or holding virtual workshops. In 2026, a hybrid approach continues. For example, a city arts center might live-stream certain community concerts or student recitals, allowing those unable to attend to still participate. It’s another way of increasing access and demonstrating the venue’s role as a cultural hub beyond its four walls.

Building Community Advocacy and Support

When a community feels pride and ownership in a venue, they become its best advocates. This can be crucial, especially when the venue faces challenges like budget cuts or opposition to a project. How do you build that kind of broad support? Through continual engagement and demonstrating tangible value to local residents.

One effective tactic is hosting open house events. Many municipal venues hold an annual open day where anyone can come explore backstage, try out instruments, meet the staff, etc., all for free. These events demystify the venue and create personal connections. A parent might bring a child to see how stage lights work, or an elderly resident might step onto the stage they’ve only seen from the seats – such experiences turn passive citizens into passionate fans of the venue.

Another approach is involving the community in decision-making in small ways. Some venues have had success with public voting or suggestion schemes for programming (“You Choose the Movie Night” or a poll for which local band should open the summer festival). When people see their input reflected, they feel a stake in the venue. In the social media age, engaging the public in this way also generates online buzz and free marketing. As noted in marketing playbooks, collaborative campaigns that involve audiences in event decisions can significantly boost engagement. For a city-owned venue, this co-creation not only fills seats but also strengthens the argument that the venue is by the people, for the people.

Community advocacy groups or “Friends” organizations often form naturally around beloved venues. Management should nurture these groups. If there isn’t one, consider helping to start a Friends of The Venue club. These are the folks who will write letters to the editor or speak at council meetings in support of the venue when needed. They can also organize volunteer efforts – like fundraising galas, neighborhood clean-up days around the venue, or hospitality for artists (some Friends groups bake cookies or provide local tours for visiting performers, adding a personal touch that touring acts remember about the city).

A vivid recent example of community advocacy can be seen in the independent venue world: during COVID, grassroot movements like #SaveOurStages in the US and the Music Venue Trust’s efforts in the UK rallied public support to save venues from closure. City-owned venues benefited too, as citizens broadly voiced that venues are vital community assets. Now in 2026, that energy can be channeled into more proactive support. Many councils have since declared music venues and theaters as protected cultural assets, acknowledging their importance beyond just balance sheets. A municipal venue operator should capitalize on this momentum – keep telling your success stories, invite testimonials from local artists and audience members, and make sure the community’s love for your venue is visible and heard. It creates a protective buffer around your venue; if someone proposes repurposing the building or slashing the budget, they’ll have an army of locals to contend with.

Ultimately, the venue’s success is inseparable from community support. A city-owned hall might not have the glitziest new tech or the biggest stars compared to a private mega-venue, but what it has is a loyal community that sees it as their place. That loyalty is earned through years of trust-building, consistency, and genuine engagement. Keep proving that the venue exists to enrich the life of the city, and the city will enrich the life of the venue in return.

Operational Excellence Under Public Scrutiny

The nuts and bolts of running a venue – ticketing, staffing, maintenance, safety – all take on a special importance when you operate in the public sector. There’s an imperative to run a tight ship because any failing can become a public issue. Here we focus on key operational areas where municipal venues must excel and how to do it.

Staffing, Training, and Labour Relations

Many city-owned venues have staff who are municipal employees or are part of public sector unions. This reality brings strengths and constraints. You often get a dedicated team (some employees stick around for decades, becoming institutional knowledge bearers), but you may face rigid job classifications and labor rules. Overtime, scheduling, and work rules might be governed by union contracts or city HR policies rather than solely by the venue manager.

To thrive in this environment, experienced managers invest heavily in staff training and morale. Well-trained employees are more efficient and can adapt to different roles as needed. Cross-training is a lifesaver in a pinch: for instance, if sound technicians are unionized and you can’t easily call in freelancers, having a junior staffer who’s been trained to assist with basic A/V duties can keep the show running during a staff shortage. In 2026, many venues also have to navigate staffing shortages and the after-effects of Covid (some older workers took early retirement, others left the industry). Recruiting young talent into public venue jobs means highlighting the benefits (stability, benefits, the pride of serving the community) and then mentoring them through the learning curve of both arts management and public sector process.

Labour relations are a major part of operations. Keeping a good relationship with unions (if present) is critical. Open communication and respect go a long way – involve crew and staff early when planning changes that affect working conditions. For example, if you’re extending operating hours for more events, talk to staff reps about how to fairly distribute the workload or compensation. Many public venues also adhere to higher labor standards by law (minimum wage laws, safety regulations, etc.), which can actually be a positive – it sets a baseline of professionalism and safety that you can tout. Some private venues cut corners on staffing costs at the expense of service; a city venue usually cannot, and the result can be a better patron experience due to well-staffed front of house and security.

That said, there are productivity hacks that don’t violate any rules: using volunteers for certain roles (like ushering) to complement staff, or students from local colleges (some performing arts management programs require internship hours – a great source of enthusiastic help). Many historic theaters have volunteer docent programs where retirees give venue tours or assist on big events, which both engages the community and lightens the load on paid staff for non-core tasks.

Another aspect is scheduling: city HR might limit how many hours per week part-timers can work or require certain breaks. Advanced planning and a pool of on-call staff can solve these issues. Technology can assist too – modern staff scheduling software (integrated with payroll systems the city uses) can cut down admin work and ensure compliance with labor rules automatically. Training staff on new tech or procedures is itself a task; following strategies to train event staff on new technology smoothly can help avoid the dreaded scenario of a new ticket scanner system failing on show night because staff weren’t comfortable using it.

In short, treat your workforce as a valued part of the mission. Happy, knowledgeable staff not only operate more efficiently – they become ambassadors of the venue’s values. A patron’s interaction with a friendly, well-informed usher or a helpful box office clerk can cement a positive reputation that reaches city hall. Many municipal venue managers proudly note that their staff’s public service mindset (versus a “just business” approach) is what sets their venue apart in customer satisfaction scores.

Maintenance, Preservation, and Capital Projects

City-owned venues often reside in older, sometimes historic buildings that require diligent maintenance and periodic renovation. Even newer state-of-the-art civic venues need upkeep. The challenge is securing funding and scheduling work without major disruptions. The public sector context adds layers: preservation laws might apply, and capital funding often comes from separate bond measures or government budgets.

Preventive maintenance is your friend. A savvy venue manager will have a detailed maintenance schedule and a capital improvements plan that looks 5-10 years ahead. For instance, if you know the roof will need replacement in five years, start the lobbying and budgeting process now. Nothing is worse than letting a facility deteriorate to the point of emergency closures – that’s a PR nightmare and a community letdown. We’ve sadly seen cases where grand theaters had to shut doors for repairs because upkeep was deferred too long. Don’t let that be your venue. Regularly update city officials on the state of the building: some even hold annual walkthroughs with council members or facilities management heads to point out needed work in person (it’s easier to get funding for a new HVAC when a councilor has just felt the venue’s old air conditioning struggling on a hot day!).

Historic venues carry additional responsibility. If your venue is a heritage building, there may be legal requirements to preserve certain architectural elements or consult with historical commissions on changes. Embrace this as part of the venue’s charm and story. Many municipal theaters built in the 1920s or 30s have undergone restorations that became source of civic pride, often funded by a mix of public money and private donations. For example, a city might allocate funds to restore a landmark theater’s façade or marquee, knowing it’s not just about the venue but the city’s cultural heritage. It’s useful to remind stakeholders that maintaining a historic venue is like preserving a piece of the city’s identity – and often, restoration projects can themselves garner positive press and community excitement (people love to see the “before and after” of a gilded age theater brought back to life).

When it comes to major capital projects (like expansions, technology overhauls, new seating, etc.), planning and communication are paramount. Usually, these projects have to be timed in off-seasons or require temporary closures. Keep the public informed well in advance: press releases, signage at the venue, email newsletters to patrons – all should explain what’s happening and why it will make their future experience better. If the venue will be closed for months, try to arrange alternate venues for key community events so those aren’t cancelled outright (maybe a partnership with a nearby school auditorium or a tented outdoor solution). Continuity maintains goodwill; people will tolerate a closure if you still facilitate the events they care about somehow.

A shining example of careful planning was during the multi-year renovation of the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London – the operators scheduled works in phases and moved some programming to other halls in the Southbank Centre complex, ensuring that artists and audiences had alternatives. Similarly, the iconic Sydney Opera House managed to remain open throughout its $202m renovation (2016-2022) by staggering work and keeping the public informed, ensuring the Opera House remained open throughout renovations. The lesson: treat renovations as part of the venue’s ongoing story, not as an inconvenience. When done, celebrate it! A grand re-opening event with community involvement reaffirms the venue’s importance and showcases the improvements that public money enabled.

Safety, Security, and Compliance

Safety in a public venue is absolutely paramount – not only is it a moral and legal obligation, but any incident is magnified under public ownership. Governments and citizens have zero tolerance for lapses that endanger lives or health. Therefore, municipal venues in 2026 are often ahead of the curve on safety protocols, adhering to strict standards and often piloting new measures.

Crowd Management: By 2026, global standards like the IFC and NFPA guidelines are well known in the venue industry. Many jurisdictions require trained crowd managers for large events. For example, fire codes often mandate at least one trained crowd manager per 250 attendees, a standard cited by Fire Systems regarding crowd safety responsibility and Frederick County crowd management training guidelines in assembly occupancies. Public venues generally comply and sometimes even exceed these requirements. Managers ensure that staff (or volunteers) are assigned to monitor crowds, keep exits clear, prevent overcrowding in sections, and implement emergency evacuation if needed. Some venues partner with local fire marshals to do annual crowd management training refreshers – a practice highly recommended. The stakes are high: nobody wants a tragedy like a crowd crush, and city officials certainly don’t want it happening in a city-run facility. Resources such as preventing dangerous crowd surges and ensuring fan safety provide up-to-date tactics like improved crowd flow design, real-time monitoring via CCTV and AI, and pre-event communication to patrons on safety rules.

Emergency Preparedness: Municipal venues typically have detailed emergency action plans. These cover scenarios from fire alarms to medical incidents to security threats. Staff drills are common – some venues hold full evacuation drills with staff (and sometimes even with the audience on special “test” days). Being public, you may also be expected to serve as an emergency shelter or assembly point for the city in case of disasters, so plans could extend beyond show-related incidents. Ensure coordination with local police, fire, and EMT services; invite them to do walkthroughs of your venue and pre-stage plans for where they’d set up incident command if something happened. Post-2020, health emergencies are also on the radar – venues now have stockpiles of PPE, touch-free sanitizing stations, and protocols for handling outbreaks (like if someone shows symptoms of illness at an event). These health safety measures are now a normal part of operations, often guided by public health departments.

Security: Threats like terrorism or active shooters, however rare, must be planned for. Municipal venues often have an edge: they can coordinate closely with law enforcement (sometimes city security or police are directly on site for major events). Bag checks, metal detectors, and surveillance systems were increasingly common in the 2020s and by 2026 even mid-size theaters have implemented them for high-profile events. The public generally accepts these as necessary – especially at publicly owned venues which they trust to be looking out for everyone’s safety. Cybersecurity is another emerging concern: venues handle ticketing data and IT networks for lighting/HVAC, etc. A city venue might fall under municipal IT security policies, which is good because it brings in resources to secure networks from hacking or ransomware (an unfortunate new threat in recent years). Ensuring robust data protection policies to safeguard patron information isn’t just about compliance with laws like GDPR, but also about maintaining public trust that buying a ticket or signing up for a newsletter at a city venue won’t expose someone’s personal data.

Compliance with Laws and Regulations: From ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) or equivalent accessibility laws abroad, to fire codes, liquor licensing, noise ordinances, and beyond – public venues must comply to the letter. Accessibility is particularly non-negotiable: city venues should be shining examples of inclusive design. This means wheelchair access to all public areas, ample accessible seating (often in excess of minimum code to accommodate demand), hearing induction loop systems or captioning for the hearing-impaired at performances, and even staff training on assisting patrons with disabilities. Many venues in 2026 also provide sensory-friendly accommodations (like quiet spaces for neurodiverse individuals to take a break from overstimulation) and ensure restrooms and amenities are inclusive (family restrooms, changing stations, etc.). If your venue is older and lacks some of these, making the necessary upgrades should be a priority in capital planning – not only for legal compliance but because it’s the right thing to do for public service.

Environmental and safety inspections should be welcomed, not feared. Fire inspectors, health inspectors, building code inspectors will show up periodically. A great tactic is to build a rapport with them – invite them to walk through and advise anytime. If you treat them as partners helping you achieve excellence, they’re more likely to give warnings or advice before issues become violations. For instance, if local code requires certain door hardware for fire exits, an inspector who knows you well may mention a worn-out door closer that needs replacement coming up, rather than writing it up after it fails. Being proactive and responsive in all matters of compliance reinforces the image that your venue is in good hands. It’s reassuring to the public and your bosses alike.

One must also remember that compliance extends to the less thrilling paperwork side: music licensing (ensuring your venue pays the necessary ASCAP/BMI/PRS fees so songwriters get their royalties) and insurance requirements (the city likely has mandated coverage levels and risk management protocols). Skipping these is never an option – a municipal venue cutting corners on paying music royalties, for example, would be a scandal. As a reminder, resources like keeping your venue legal with music licensing in 2026 can help managers stay on top of obligations to artists and rights organizations. It’s all part of running an ethical, law-abiding operation that citizens can be proud of.

In sum, operational excellence in a city-owned venue is about anticipation and diligence. If something can go wrong, plan for it, and plan to prevent it. When you do this consistently, not only do you avoid crises, you also make day-to-day events run smoother. And when things run smoothly, patrons have a great experience, artists love coming back, the media has nothing negative to report, and the city officials hear only good news – a virtuous cycle reinforcing the venue’s value.

Embracing Innovation for Public Venues

Just because a venue is city-owned doesn’t mean it should be stuck in the past. In fact, many municipal venues are leading the way in adopting new technology and innovative practices to enhance both operations and audience experience. In 2026, embracing innovation is key to staying relevant and efficient.

Adopting Modern Ticketing and Audience Tech

Ticketing is one area where significant advances have been made. Gone are the days of paper tickets in many places – mobile ticketing, biometric entry, and blockchain ticketing are making inroads. Municipal venues often cater to a wide demographic (from teens to seniors), so any ticketing solution must be user-friendly and inclusive. Many are opting for hybrid systems: digital tickets for those comfortable with them, but still offering a physical or print-at-home option for the less tech-savvy. The goal is a seamless entry experience that doesn’t turn anyone away.

Selecting the right ticketing platform can greatly impact a venue’s finances and patron data. Some older municipal venues were locked into legacy systems (maybe due to long contracts or the assumption that a government venue had to use a certain provider). Now, managers are re-evaluating these deals. Key factors include fees, control of customer data, and flexibility of features. A forward-looking venue might consider an innovative platform like Ticket Fairy that prioritizes transparent pricing and rich marketing tools. For instance, Ticket Fairy’s platform notably has no dynamic pricing, aligning with public venues’ need to keep pricing fair and predictable for patrons. It also offers features like referral marketing (boosting word-of-mouth sales) and face-value ticket resale which prevents scalping issues. Such features can be a boon to city venues that want to ensure equitable access – imagine allowing fans to resell tickets they can’t use, but only at face value or less, so tickets to that popular community concert don’t end up triple-priced on secondary markets.

Data ownership is another consideration. Many municipal venues now insist on any ticketing system giving them full access to customer contact info and purchase history (within privacy law bounds). This data can feed CRM systems, loyalty programs, or simply better tailor offerings. If your current system keeps patron emails to itself or charges extra to run a marketing campaign to your ticket buyers, it might be time to shop around. A comparison of ticketing platforms on fees, data control, and fan features can be enlightening – some newer systems have far more favorable terms for venues than the big old ticketing giants.

Beyond ticketing, audiences in 2026 expect tech-enhanced experiences. City venues are experimenting with things like venue mobile apps that offer digital playbills, interactive venue maps, and even food ordering to your seat. While a full-fledged native app may be overkill for a small theater, many are using progressive web apps (PWAs) or integrating features into the ticketing web interface to achieve similar results without requiring downloads. By making information accessible on personal devices, venues reduce print costs (fewer paper programs), improve accessibility (font size adjust, screen readers for content), and can push real-time updates (like “Show starts in 10 minutes” or “Intermission now, visit the lobby bar for a special drink”).

Cashless payments are another innovation wave. Post-pandemic, many venues accelerated the move to cashless for speed and hygiene. City venues must ensure alternatives are available for those without cards (some jurisdictions legally require accepting cash to not disadvantage certain groups), but largely cashless systems have cut queues and improved revenue per cap. Integrating with city-wide payment apps or transit cards is even happening in some places (imagine tapping your metro card to buy a drink at the theater – convenient!).

While integrating transit passes offers incredible convenience, it also introduces new security considerations for the venue’s IT and front-of-house teams. Operators must collaborate with local transit authorities to ensure point-of-sale terminals are secure, actively protecting patrons against risks like metrocard theft or digital pickpocketing in crowded lobby areas. Safeguarding these integrated payment methods is just as critical as securing the primary ticketing database.

Enhancing the Audience Experience

Today’s audiences crave experiences, not just events. Municipal venues are thus experimenting with creative ways to make a night at the theater or concert hall more memorable. One trend is creating Instagrammable moments within the venue. You might have seen modern art museums or trendy clubs do this, but even a civic venue can play: perhaps a beautiful mural wall or a historic prop on display where people can snap photos, or seasonal decorations that invite selfies. By turning the venue itself into a social media sensation, you get free marketing as attendees share their experiences online – and it can attract younger crowds who love visually driven outings.

Interactive technology is also making its way into live shows. Some municipal performing arts centers have started using augmented reality (AR) in subtle ways. For example, providing AR glasses to overlay translations or captions during an opera (rather than the old supertitle screens), or using AR apps for educational enhancements – like pointing your phone at a display in the lobby to see a 3D model of the theater’s architecture popping up with historical facts. Venues are also dabbling with gamification to engage audiences. A city-run amphitheater might run a scavenger hunt via a mobile app during a music festival it hosts, encouraging attendees to explore different stalls or historical markers on site in exchange for digital badges or small prizes. Such layers of interactivity can elevate the experience beyond just passive watching.

Another arena of innovation is programmatic. Some forward-thinking municipal venues are blending genres or creating new event formats to draw interest. Think concerts with immersive projections, or theater in the round with audience participation segments. While high-tech shows are often the domain of avant-garde companies, city venues can partner with creative tech startups or university programs to pilot such shows. It positions the venue as an innovator. In cities like Amsterdam and Tokyo, municipal arts venues have hosted mixed reality performances where holographic elements or live digital painting happen as part of the show – attracting not only art lovers but also tech enthusiasts.

Audience comfort and convenience are also being upgraded. Following in the footsteps of sports stadiums, some concert halls are adding features like smart seating (seats that can vibrate with the bass – a novelty for concerts, or simply more spacious seating with tablet stands for conferences), or upgraded amenities like nursing lounges for mothers, gender-neutral restrooms, and water bottle refill stations. These might seem mundane compared to AR, but they send a message of inclusivity and thoughtfulness that resonates with the public mandate to be welcoming to all.

Sustainability and Green Initiatives

City governments worldwide are making climate action a priority, and municipal venues are part of that push. Embracing sustainability is not only socially responsible but can also reduce long-term operating costs and appeal to eco-conscious audiences.

Many city-owned venues are embarking on green upgrades: LED lighting retrofits on stage and in-house, solar panels on roofs or parking structures, energy-efficient HVAC systems, and water-saving fixtures. While the upfront cost can be high, public grants or green bonds often help finance these, and the long-term savings in utility bills are significant for a facility that might be large and power-hungry. Some venues have achieved remarkable transformations – for instance, the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall implemented a building management system that cut energy use by over 30% within a few years, by smartly controlling when systems run.

Another visible trend is tackling waste. Single-use plastics are on the way out at many public venues. By 2026, it’s common for a city venue’s bar to serve drinks in compostable cups or sell reusable souvenir cups that double as a nice takeaway. Recycling and compost bins are placed next to every trash can, with clear signage. Some venues partner with local zero-waste organizations to audit their operations and suggest improvements. Even on the production side, venues are encouraging greener practices: things like eco-certified cleaning products, rechargeable batteries for wireless mics (rather than burning through thousands of disposables), and digital rather than paper for as many documents as possible (light plots, schedules, even scripts in rehearsals can be on tablets now).

One creative initiative is carbon offset programs tied to events. A municipal auditorium might allow patrons to add $1 to their ticket to go toward planting trees or investing in renewable energy – an easy upsell that guilt-free concertgoers and helps the city meet sustainability goals. Some venues themselves purchase offsets for particularly electricity-heavy events or aim for carbon-neutral certifications. It’s a great PR point to say “Our 2026 season is fully carbon-neutral,” but such claims must be backed by real action to avoid greenwashing accusations (especially as a public entity, transparency is key).

Additionally, focusing on sustainable transport for events is rising. Venues encourage attendees to take public transit (maybe partnering with transit authorities to include free or discounted rides with an event ticket, or simply highlighting transit options in communications). Bike parking and even electric vehicle charging stations at venues are becoming common amenities. All these efforts not only help the environment but also strengthen the venue’s image as a modern, responsible community member.

Accessibility and Inclusive Design

We touched on ADA and accessibility earlier as compliance, but beyond the basics, truly inclusive design strives to make everyone feel welcome and catered to. Municipal venues often lead here because serving the whole public is literally their job.

In 2026, accessibility goes beyond physical. Venues are broadening the concept to include sensory and cognitive inclusion. For example, “sensory bags” with items like noise-canceling headphones, fidget tools, and sunglasses might be available at the guest services desk for those with sensory sensitivities. Some theaters now have special seating zones where lights and sounds are a bit more restrained for sensitive audiences (or conversely, where parents with an autistic child can sit knowing it’s okay if the child makes some noise or moves around). These concepts were pioneered by certain progressive venues and are catching on as best practices.